YTC Ventures | TECHNOCRAT MAGAZINE | www.ytcventures.com

In a groundbreaking and tense chapter of space exploration, four astronauts splashed down in the Pacific Ocean off San Diego on January 15, 2026, completing NASA’s first-ever medical evacuation from the International Space Station (ISS).

The Crew-11 mission—comprising NASA astronauts Zena Cardman (commander) and Mike Fincke (pilot), JAXA astronaut Kimiya Yui, and Roscosmos cosmonaut Oleg Platonov—ended 167 days in orbit, over a month earlier than planned, due to a serious but undisclosed medical condition affecting one crew member.

The undocking occurred on January 14, with the SpaceX Crew Dragon capsule executing a flawless 11-hour reentry and splashdown at 3:41 a.m. ET. Recovery teams swiftly assisted the crew, who were all reported in good spirits upon arrival.

The affected astronaut, whose identity remains private for medical confidentiality, is “doing fine” and undergoing evaluations in a San Diego hospital. NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman emphasized that the decision prioritized safety, noting the crew member’s stable condition throughout.This event marks a pivotal moment in the ISS’s 25-year history of continuous human presence, highlighting the inherent risks of long-duration spaceflight. With the station now operating with a reduced “skeleton crew” of three (NASA’s Christopher Williams and Roscosmos cosmonauts Sergey Kud-Sverchkov and Sergey Mikaev), activities like spacewalks are on hold until the next crew arrives in mid-February.

As humanity eyes deeper space ventures to the Moon and Mars—where quick returns aren’t feasible—this evacuation underscores the need for advanced onboard medical capabilities.

The International Space Station: A Marvel of Global Collaboration

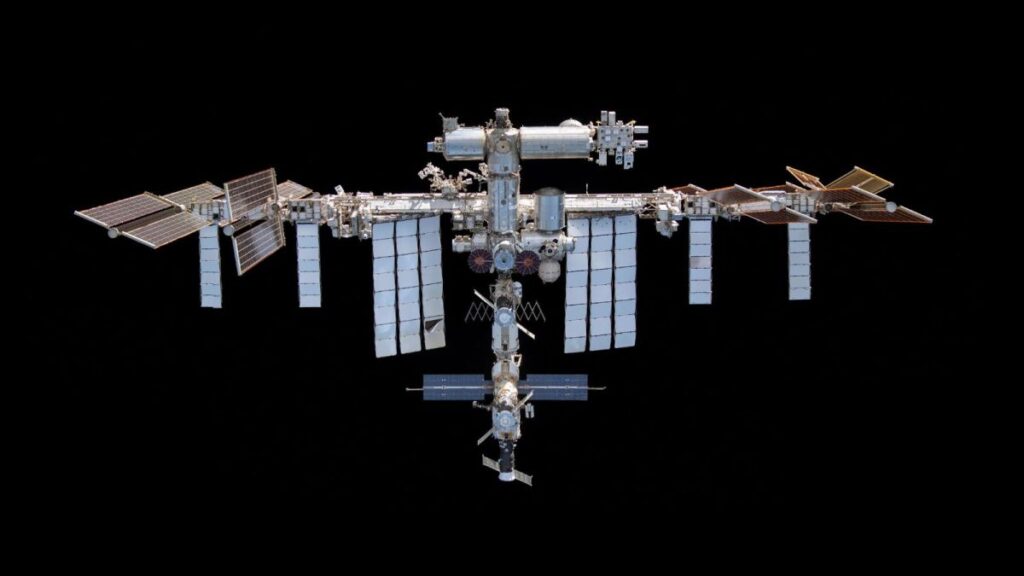

The ISS, orbiting Earth at 250 miles altitude and speeding at 17,500 mph, is humanity’s outpost in low Earth orbit (LEO). Launched in phases starting with Russia’s Zarya module on November 20, 1998, and the U.S. Unity module shortly after, the station has been continuously occupied since November 2, 2000—celebrating 25 years of habitation in 2025.A collaborative effort by five space agencies—NASA (U.S.), Roscosmos (Russia), ESA (Europe), JAXA (Japan), and CSA (Canada)—the ISS spans 109 meters (358 feet) end-to-end, roughly the length of a football field, with a mass of about 450,000 kg (990,000 lbs).

It features six sleeping quarters, two bathrooms, a gym, and a 360-degree bay window for stunning Earth views. The habitable volume is over 916 cubic meters, larger than a six-bedroom house.Assembly required 42 flights: 37 by U.S. Space Shuttles and five by Russian rockets. It orbits Earth every 90 minutes, hosting up to seven crew members for expeditions lasting up to six months.

Over 300 astronauts from nearly 20 countries have visited, conducting thousands of experiments in microgravity across biology, physics, and technology—paving the way for future deep-space missions.

The Staggering Costs: Building and Sustaining Humanity’s Orbital Lab

The ISS represents one of the most expensive human endeavors ever, with a total construction cost estimated at $150 billion, shared among international partners.

Europe’s contribution alone was about €8 billion, equating to roughly €1 per European citizen annually—less than a cup of coffee.Annual maintenance and operations are equally hefty. NASA allocates around $3-4 billion yearly, covering systems upkeep ($1.1 billion), crew and cargo transportation ($1.7 billion), and research ($350 million).

This includes preventive and corrective maintenance, upgrades (like battery replacements), and resupply missions. Recent challenges, such as cracks in the Russian Service Module, have driven upgrade costs up 35% in recent years.As the ISS nears its planned retirement around 2030, deorbiting costs add another layer—potentially billions more for a controlled descent to avoid space debris risks.

These investments have yielded invaluable data, but they highlight the economic hurdles for future stations.

Past Medical Evacuations: A Rare but Critical History

While this 2026 event is the first medical evacuation from the ISS in its 25-year history, space stations have seen health-related early returns before—mostly during the Soviet era. NASA’s models predicted an evacuation every three years, yet none occurred until now.Here’s a summary of notable past space station medical evacuations:

| Year | Space Station | Crew Member(s) Affected | Issue | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1985 | Salyut-7 (Soviet) | Vladimir Vasyutin and crew | Urological infection/illness | Mission cut short by four months; early return after 64 days in orbit. |

| Pre-1985 (Various) | Soviet stations (e.g., Salyut series) | Multiple cosmonauts (details limited) | Less serious health issues (e.g., infections, fatigue) | Shortened flights; no full evacuations detailed in public records. |

These incidents, primarily from the 1970s-1980s Soviet program, involved infections or related illnesses prompting abbreviated missions. No such events occurred on Mir (1986-2001) or the ISS until 2026, thanks to improved medical screening and onboard facilities. This rarity emphasizes the robustness of modern space medicine but reminds us of microgravity’s toll on the human body.

The Crew-11 evacuation showcases the seamless international cooperation and SpaceX’s reliability that define the ISS era. As we transition to commercial stations and lunar outposts, lessons from this event will fortify future explorations. Welcome home, Crew-11—your safe return is a testament to human resilience in the stars!

Comments