By YTC Ventures History Insights | October 2, 2025

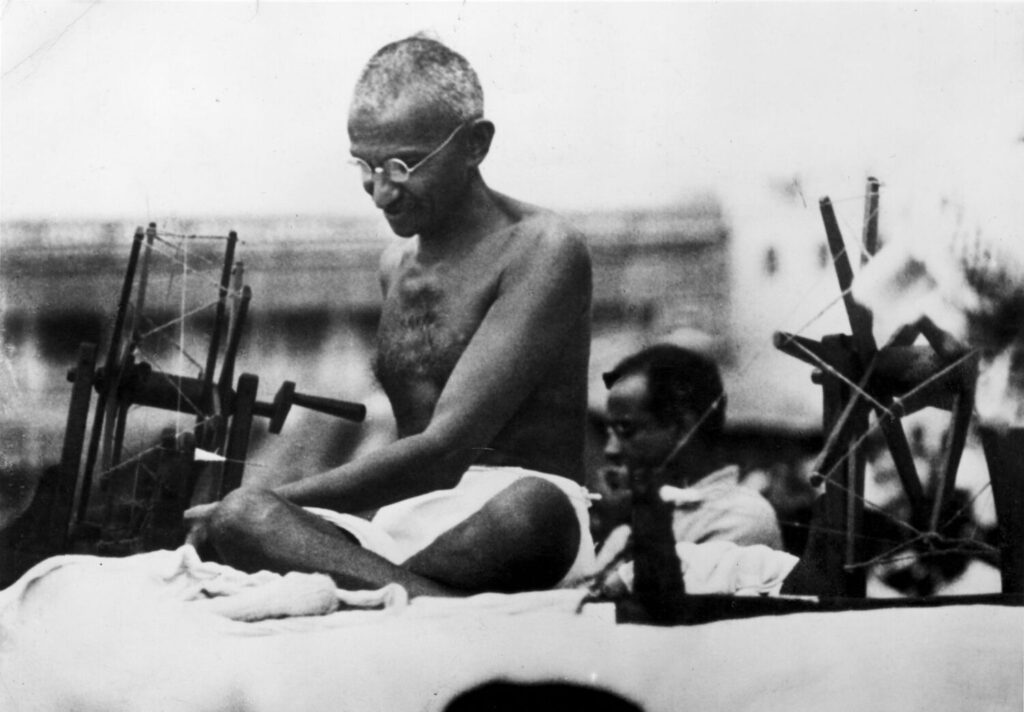

Today, October 2, marks the 156th birth anniversary of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi—affectionately known as Mahatma, or “Great Soul”—the architect of India’s independence through nonviolent resistance. Born in 1869 amid the British Raj’s iron grip, Gandhi’s life was a tapestry of profound triumphs, searing controversies, and personal experiments that continue to provoke debate.

From his humble beginnings in Porbandar, Gujarat, to his assassination in 1948, Gandhi embodied the principle of satyagraha (truth-force), influencing global leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and Nelson Mandela. Yet, his path was fraught with blunders, ideological clashes, and a complex relationship with power, money, and society.This comprehensive tribute delves into Gandhi’s education and family life, his early career, the missteps that humanized him, his monumental on-the-ground works, his philosophy on wealth and greed, and the tragic motivations behind his murder by Nathuram Godse.

Drawing from historical records and Gandhi’s own writings, we honor a man whose light still guides the quest for justice—while confronting the shadows that linger.

Early Life: Roots in Faith, Family, and Formal Education

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi entered the world on October 2, 1869, in Porbandar, a coastal princely state in Gujarat, as the youngest of four children born to Karamchand Uttamchand Gandhi and his fourth wife, Putlibai. Karamchand, a devout Hindu and diwan (chief minister) to the local ruler, embodied modest administrative service under British suzerainty, while Putlibai, from a Pranami Vaishnava family, instilled in young Mohandas a deep piety marked by fasting, temple visits, and vegetarianism.

The family’s Vaishnavist traditions—emphasizing nonviolence, truth, and devotion—shaped Gandhi’s worldview, though he later drew from Jainism, Christianity, and Islam.Gandhi’s formal education began at a local Gujarati school, where he was an average student, excelling more in character than academics. He matriculated from high school in Ahmedabad in 1887 but struggled at Samaldas College in Bhavnagar, dropping out after one term due to health issues and homesickness.

Undeterred, in 1888, at age 18, he sailed to London to study law at University College, supported by family friend Mavji Dave Joshi. There, Gandhi navigated cultural shocks—adopting Western suits while pledging to his mother to abstain from meat, alcohol, and women—earning his barrister qualification in 1891.

This period honed his discipline and exposed him to Western liberalism, though he later critiqued its materialism.

Family Life: A Partnership of Trials, Love, and Sacrifice

Gandhi’s personal life was as austere as his public one. At 13, in a traditional arranged marriage, he wed Kasturba (Kasturbai) Makhanji Kapadia, a girl from a similar Modh Bania merchant family in Porbandar. Their union, spanning 62 years until her death in 1944, was marked by deep affection amid conflicts—Gandhi admitted to youthful jealousy and possessiveness, once physically barring her from visiting her family.

Kasturba, illiterate at marriage but later taught by Gandhi, became his steadfast partner in activism, enduring arrests and exile while managing the household.The couple had five children: their firstborn died days after birth in 1885, followed by sons Harilal (1888–1948), Manilal (1892–1956), Ramdas (1897–1969), and Devdas (1900–1957).

Gandhi’s parenting was rigorous; he prioritized moral education over material comforts, enforcing vegetarianism and celibacy experiments that strained family bonds. Harilal’s rebellion—converting to Islam and disowning his father—epitomized the rift, with Gandhi viewing it as a test of his principles.

Despite tensions, Kasturba’s unwavering support during South African struggles and India’s Quit India Movement underscored their shared sacrifice; she died in detention at Aga Khan Palace in 1944, whispering Gandhi’s name.

Work Life and the Spark of a Career: From Barrister to Activist

Returning to India in 1891, Gandhi’s legal career faltered in Bombay and Rajkot, where his shyness and ethical qualms hindered courtroom success.

A turning point came in 1893: at 23, he accepted a one-year contract with Dada Abdulla & Co., an Indian trading firm in Durban, South Africa, to represent a cousin in a lawsuit.South Africa (1893–1914) forged the activist. En route to Pretoria, Gandhi was ejected from a first-class train compartment for being “colored,” igniting his fight against racial discrimination.

He founded the Natal Indian Congress in 1894, petitioning against disenfranchisement laws, and launched Indian Opinion newspaper in 1903 to rally the Indian diaspora. Experiments in communal living at Phoenix Settlement (1904) and Tolstoy Farm (1910) tested his ideals of self-sufficiency and nonviolence.Gandhi’s satyagraha debuted in 1906 against the Asiatic Registration Act (“Black Act”), leading passive resistance campaigns that mobilized thousands, including women like Kasturba. By 1914, concessions like the Indian Relief Act marked his first major victory, earning him global acclaim.

Returning to India in 1915 as “Mahatma,” he joined the Indian National Congress, transforming it into a mass movement.

Blunders and Controversies: The Flawed Human Behind the Saint

Gandhi’s halo obscures his humanity. Critics highlight his early racial views in South Africa, where he campaigned for Indian rights but derogatorily called Black Africans “kaffirs” and prioritized Indians over them, later evolving but never fully recanting.

His stance on caste drew ire: while anti-untouchability, he opposed separate electorates for Dalits in the 1932 Poona Pact, clashing with B.R. Ambedkar, whom he fasted to coerce—seen by some as paternalistic.

Sexuality experiments post-1906 celibacy vow shocked: in his 70s, Gandhi slept naked with young women, including grandnieces, to test brahmacharya (celibacy), admitting arousal but denying impropriety—a practice that alienated associates like Vallabhbhai Patel.

Partition (1947) was a perceived blunder; his concessions to Muslim League demands, per detractors, enabled violence killing a million.

Khilafat Movement alliance (1919–1924) with pan-Islamists backfired into riots, costing Hindu lives.

Gandhi’s “Seven Social Sins”—wealth without work, pleasure without conscience—ironically mirrored his own: favoring Nehru over Bose, and experimental fasting that critics called manipulative.

These controversies—racism, misogyny, caste paternalism—paint Gandhi as flawed, not infallible, fueling modern debates in India where statues are vandalized and his image politicized.

Great Works on the Ground: Satyagraha in Action

Gandhi’s legacy shines in tangible campaigns. In Champaran (1917), he exposed indigo planters’ exploitation, forcing British concessions via inquiry and peasant education.

Kheda (1918) saw no-tax satyagraha amid famine, securing revenue waivers.

Non-Cooperation (1920–1922) boycotted British goods, schools, and courts, swelling Congress ranks to millions—halted after Chauri Chaura violence.

The 1930 Salt March—240 miles to Dandi—defied salt monopoly, sparking mass arrests and global sympathy.

Quit India (1942) demanded immediate independence, jailing leaders but galvanizing the masses.Socially, Gandhi built ashrams promoting khadi (homespun cloth) for economic self-reliance, Harijan upliftment, and women’s empowerment—Kasturba led satyagrahas.

His 1947 fast quelled Delhi riots, averting total collapse.

These ground-level mobilizations dismantled colonial fear, birthing a free India on August 15, 1947.

Gandhi and Money: A Philosophy of Simplicity, Not Greed

Gandhi abhorred greed, famously stating, “The world has enough for everyone’s need, but not for everyone’s greed.”

Born to modest means, he renounced wealth post-South Africa, living on donations and khadi labor. In Hind Swaraj (1909), he critiqued industrialization as exploitative, advocating village economies where wealth served dharma (duty), not artha (profit).

Greedy? No—Gandhi was ascetic, spinning his own cloth and fasting for causes. He viewed money as a tool for trusteeship: the rich as stewards for the poor.His ashrams practiced self-sufficiency, rejecting luxury. Yet, critics note his control over Congress funds raised ethical questions, though never personal enrichment.

Gandhi’s ethos: wealth without work is sin; simplicity fosters true freedom

Why Godse Shot Him: Ideological Fury and the Clash of Visions

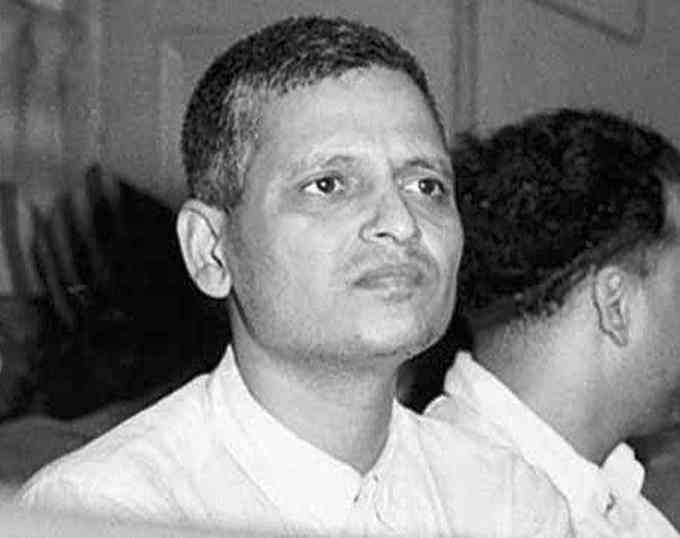

On January 30, 1948, at Birla House, Delhi, Gandhi—frail at 78—was shot three times by Nathuram Godse during a multi-faith prayer. Godse, a Hindu nationalist, saw Gandhi as a betrayer.

In his court statement, Godse accused Gandhi of Muslim appeasement: supporting Khilafat, conceding to Pakistan’s creation (causing Hindu suffering in Partition riots), and fasting for Indian Muslims while ignoring Pakistani Hindus.

Godse viewed nonviolence as weakness enabling “Hindu genocide,” per his Why I Assassinated Mahatma Gandhi.

The act stemmed from Hindutva ideology—Gandhi’s secularism clashed with Godse’s vision of a Hindu Rashtra. Previous attempts (1944 knife, 1948 grenade) failed; this succeeded amid post-Partition chaos.

Gandhi’s final words: “Hey Ram.”

A Biography of Nathuram Godse: From Devotee to Assassin

Nathuram Vinayak Godse (May 19, 1910–November 15, 1949) was born in Baramati, Maharashtra, to Vinayak Vamanrao Godse, a postmaster, and Lakshmi, in a Chitpavan Brahmin family.

Superstition after three sons’ deaths led parents to raise him as a girl initially—nath (nose ring) pierced—earning his name. Schooled in English-medium Poona, he dropped out post-matric, opening a failed tailoring shop.

At 22, Godse joined RSS, imbibing Hindu nationalism, but quit in the 1930s for Hindu Mahasabha, editing Agrani (later Hindurashtra) to rail against Gandhi’s “pro-Muslim” policies.

Influenced by V.D. Savarkar, he formed the militant Hindu Rashtra Dal. Childless and unmarried, Godse’s life revolved around ideology.

Arrested post-assassination with Narayan Apte and six others (including brother Gopal), Godse’s trial revealed a conspiracy; he claimed sole responsibility, defending it as “moral duty.”

Hanged in Ambala Jail, his legacy divides: vilified then, now glorified by some Hindutva groups as patriot, with temples and plays rehabilitating him.

Gandhi’s death unified India in grief, banning RSS temporarily, but Godse’s ideas echo in today’s polarizations. On this birthday, may we heed Gandhi’s call: “Be the change you wish to see.” His flaws remind us leaders are human; his works, that nonviolence endures.

Comments