YTC Ventures | Technocrat’ Magazine

November 1, 2025

In the heart of New Delhi’s Parliament House, enshrined in a grand chamber, lies the original copy of the Constitution of India—a 251-page document adorned with exquisite calligraphy and illustrations inspired by ancient Indian art. Adopted on November 26, 1949, and effective from January 26, 1950, this living blueprint has steered the world’s largest democracy for over 75 years.

As India marks its Republic Day each year, the Constitution stands not just as a legal tome but as a testament to the nation’s resilient spirit, forged in the fires of colonial subjugation and the dreams of a billion souls. What is its story? A saga of struggle and synthesis. What is its power? The unyielding force that binds a diverse mosaic into a sovereign republic. This article delves into its origins, evolution, and enduring might.

The Genesis: From Colonial Chains to Constituent Dawn

The story of the Indian Constitution is inextricably woven into the fabric of India’s independence movement—a chronicle of resistance against British rule that spanned nearly two centuries.

The roots trace back to 1773 with the Regulating Act, the first British parliamentary step to control the East India Company’s excesses in India. This was followed by a series of acts: the Pitt’s India Act of 1784, which strengthened British oversight; the Charter Acts of 1813, 1833, and 1853, expanding trade and administration; and the Government of India Act 1858, which ended Company rule and placed India directly under the Crown after the 1857 Revolt.

The momentum built with the Indian Councils Acts of 1861, 1892, and 1909, introducing limited Indian representation in legislative councils.

The Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms of 1919 devolved some powers to provinces, while the Government of India Act 1935 laid the groundwork for federalism, provincial autonomy, and a bicameral legislature—features heavily borrowed for the final Constitution. Amid the Quit India Movement and World War II negotiations, the Cripps Mission in 1942 acknowledged Indians’ right to frame their own constitution, a pivotal concession.The turning point came with the Cabinet Mission Plan of 1946, which proposed a constituent assembly elected by provincial legislatures. Elected in July 1946, the Constituent Assembly—initially 389 members, reduced to 299 after Partition—convened for the first time on December 9, 1946, under temporary chairman Sachidanand Sinha, with Rajendra Prasad as permanent president.

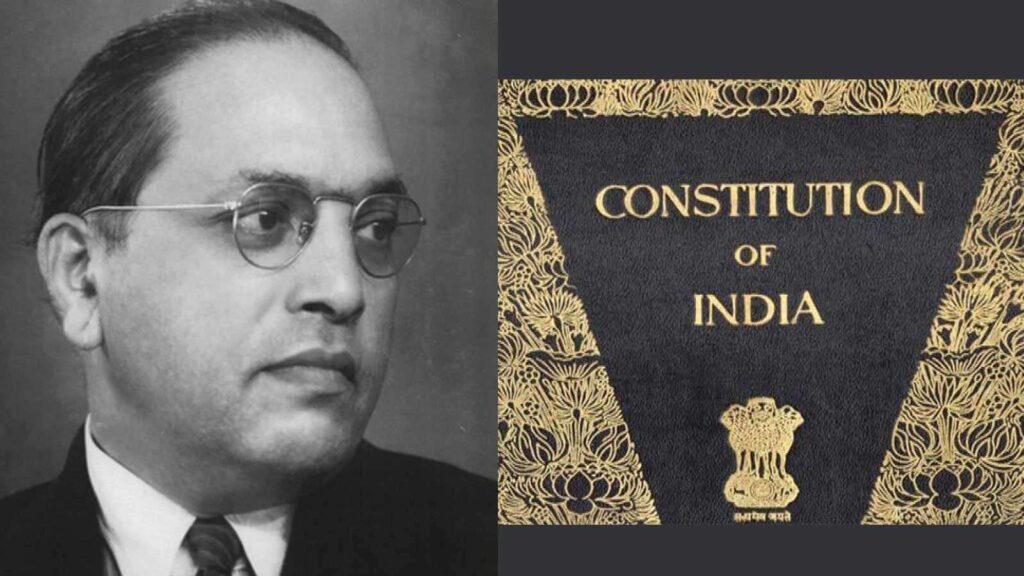

Representing the Indian National Congress, Muslim League, Scheduled Castes Federation, and others, it was a microcosm of India’s diversity, though boycotted by the Muslim League initially.Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the architect of social justice and Chairman of the Drafting Committee, led the charge. Over 2 years, 11 months, and 18 days, the Assembly held 11 sessions, debating 7,635 amendments to produce a draft with 395 articles, 22 parts, and 8 schedules—making it the world’s longest written constitution. Influences abounded: Parliamentary sovereignty from Britain, judicial review from the US, directive principles from Ireland, and federalism from Canada.

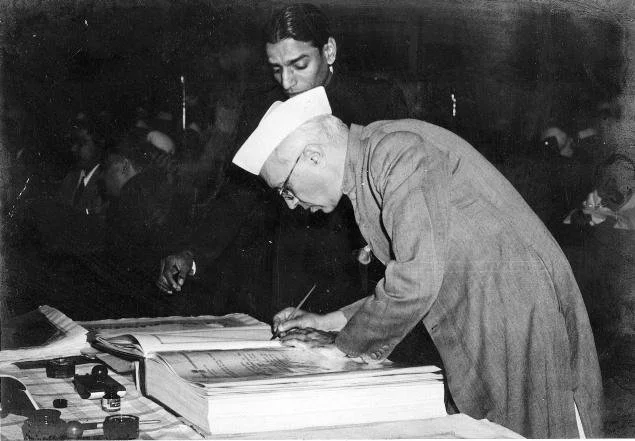

The Preamble, echoing the Objectives Resolution by Jawaharlal Nehru, declared India a “Sovereign Socialist Secular Democratic Republic” committed to justice, liberty, equality, and fraternity.On November 26, 1949—now Constitution Day—the Assembly adopted it, with Articles 5-9, 60, 324, and others effective immediately for citizenship and elections. The rest activated on January 26, 1950, commemorating the 1930 Lahore Session’s call for Purna Swaraj, transforming India from a dominion to a republic. The Indian Independence Act 1947 and Government of India Act 1935 were repealed, birthing a new era.

The Pillars: Structure and Salient Features

At its core, the Constitution is a social document, as historian Granville Austin described, blending Fundamental Rights (Part III) and Directive Principles of State Policy (Part IV) to realize egalitarian goals.

It establishes a parliamentary federal democracy with a presidential touch: The President as ceremonial head (Articles 52-73), aided by a Council of Ministers led by the Prime Minister (Article 74).Key features include:

- Length and Detail: Originally 395 articles (now 448 after amendments), 25 parts, and 12 schedules, addressing everything from citizenship to tribal areas.

- Fundamental Rights: Six in number (Articles 12-35)—equality, freedom, against exploitation, religion, cultural/educational, and remedies—enforceable by courts, inspired by the US Bill of Rights.

- Directive Principles: Non-justiciable socio-economic goals (Articles 36-51) like uniform civil code, education, and Gandhian principles, drawing from Ireland.

- Fundamental Duties: Added by the 42nd Amendment (1976), 11 duties (Article 51A) for citizens, echoing Japan’s model.

- Federalism with Unitary Bias: A “Union of States” (Article 1) divides powers via three lists in the Seventh Schedule: Union (97 subjects like defense), State (66 like police), and Concurrent (47 like education). Single citizenship and an integrated judiciary (Articles 124-147) ensure unity.

- Secularism and Universal Adult Suffrage: Added to the Preamble in 1976, it guarantees religious freedom (Articles 25-28); voting rights for all above 18 (Article 326, amended 1989).

- Independent Judiciary: The Supreme Court (Article 124) wields judicial review (Article 13), striking down unconstitutional laws, blending US and British influences.

- Emergency Provisions: Articles 352-360 allow central override during war, financial crisis, or state failure, a safeguard for national integrity.

The Power: Supremacy, Adaptability, and Social Revolution

The Constitution’s power lies in its supremacy—any law contradicting it is void (Article 13)—ensuring rule of law and protecting against arbitrary state action. It demarcates powers among legislature, executive, and judiciary (separation of powers), fostering checks and balances. Amended 106 times (as of 2023), it balances rigidity (for core features like federalism) and flexibility (simple majority for some changes) via Article 368.

The “basic structure doctrine” (Kesavananda Bharati case, 1973) shields essentials like democracy and secularism from amendment.Its significance? It has empowered marginalized voices—abolishing untouchability (Article 17), reserving seats for SC/STs, and advancing gender equality—while navigating emergencies like 1975’s internal proclamation. In a nation of 1.4 billion, it promotes unity amid diversity, with Hindi and English as official languages and 22 scheduled ones recognized.

As Ambedkar noted, it is a “social document” driving equity through rights and directives.Yet challenges persist: Over-centralization critiques, implementation gaps in directives, and debates on secularism. Still, it remains a beacon, inspiring global constitutions.

Fundamental Duties: Added by the 42nd Amendment (1976), 11 Duties (Article 51A) for Citizens, Echoing Japan’s Model

Legacy: A Living Document for Eternity

From Ambedkar’s vision to Nehru’s ideals, the Constitution embodies India’s soul—resilient, inclusive, transformative. As we reflect on its 75th anniversary, it reminds us: Power resides not in parchment, but in the people’s commitment to its promise. In an era of polarization, its call for fraternity endures, guiding India toward a just tomorrow. Jai Hind!

Illustration: The 11 Fundamental Duties as Pillars of Responsible CitizenshipImagine a grand temple of democracy, where the Constitution stands as the sanctum. Flanking its core—Fundamental Rights—are 11 sturdy pillars, each inscribed with a duty, carved in 1976 via the 42nd Amendment during a turbulent era under Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. Inspired by Japan’s post-war Constitution (Article 12, emphasizing public welfare), these duties shifted focus from “rights alone” to “duties for all,” reminding every citizen: Freedom thrives when responsibility anchors it.Here they are, visualized as 11 Pillars of Duty:

| Pillar | Duty (Article 51A) | Essence & Symbol |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Abide by the Constitution | To abide by the Constitution and respect its ideals, the National Flag, and the National Anthem. | Pillar of Loyalty – A citizen saluting the Tricolor, with the Preamble glowing behind. |

| 2. Cherish Noble Ideals | To cherish and follow the noble ideals that inspired the national struggle for freedom. | Pillar of Inspiration – Flames of 1857 Revolt, Quit India, and Gandhi’s charkha. |

| 3. Uphold Sovereignty | To uphold and protect the sovereignty, unity, and integrity of India. | Pillar of Unity – Hands from Kashmir to Kanyakumari joining in a circle. |

| 4. Defend the Country | To defend the country and render national service when called upon. | Pillar of Valor – Soldier, doctor, teacher—all in service during crisis. |

| 5. Promote Harmony | To promote harmony and the spirit of common brotherhood amongst all, transcending religion, language, region, or section. | Pillar of Fraternity – Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, Christians in a group hug under one sky. |

| 6. Value Composite Culture | To value and preserve the rich heritage of our composite culture. | Pillar of Heritage – Taj Mahal, Ajanta, Kathak, Bharatanatyam, Vedas, and folk art in mosaic. |

| 7. Protect Environment | To protect and improve the natural environment including forests, lakes, rivers, and wildlife, and to have compassion for living creatures. | Pillar of Green Duty – Child planting a tree, tiger roaming free, clean Ganga flowing. |

| 8. Develop Scientific Temper | To develop the scientific temper, humanism, and the spirit of inquiry and reform. | Pillar of Reason – Einstein-like figure with ISRO rocket, lab, and open book. |

| 9. Safeguard Public Property | To safeguard public property and to abjure violence. | Pillar of Care – No vandalism; citizens repairing a broken bench, stopping a riot. |

| 10. Strive for Excellence | To strive towards excellence in all spheres of individual and collective activity so that the nation constantly rises to higher levels. | Pillar of Aspiration – Athlete winning gold, student topping exam, farmer with record yield. |

| 11. Educate Children (Added 2002) | To provide opportunities for education to children between 6–14 years (86th Amendment). | Pillar of Future – Parent and teacher guiding a child to school (linked to RTE Act). |

Visual Metaphor: These pillars form a circle around the citizen, not to confine, but to elevate—like a garland of responsibility. Japan showed the way; India made it swadeshi.

Though non-justiciable (not enforceable by law), these duties are invoked in judgments (e.g., M.C. Mehta vs Union of India for environment) and taught in schools to nurture conscious citizenship.

As Ambedkar warned: “Constitution is only as good as the people who work it.” These 11 duties? The people’s promise to keep it alive.

Comments