The Business of Whaling

Whaling was a cornerstone of global commerce from the 17th to the 19th centuries, particularly in the United States, where it became a dominant industry in New England by the 19th century. Driven by demand for whale oil (used for lighting and lubrication), spermaceti (for candles), and baleen (for corsets and other products), whaling was a high-risk, high-reward enterprise.

At its peak in the 1840s–1850s, the U.S. whaling industry, centered in Nantucket and New Bedford, Massachusetts, contributed $10 million annually to the GDP, making it the fifth-largest sector of the economy.

By 1850, American ships comprised nearly 75% of the world’s 900 whaling vessels, showcasing U.S. dominance in this global trade.

Whaling voyages were perilous, often lasting 3–4 years or even a decade, with crews facing storms, hostile encounters, disease, and aggressive whales. For example, the Essex was sunk by a sperm whale in 1820, inspiring Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick. Despite the risks, the potential for outsized returns—sometimes exceeding 100% on a single voyage—drove investment and innovation, making whaling a precursor to modern venture capital.

The First Stock Market: Whaling’s Financial Innovation

While not a stock market in the modern sense, the whaling industry pioneered a financial structure that resembled early stock markets. Whaling ventures required significant capital—$20,000 to $30,000 per voyage (equivalent to $500,000–$750,000 today), far more than the average farm ($2,500) or manufacturing firm ($5,000).

To fund these costly expeditions, whaling agents divided ship ownership into fractional shares (e.g., 1/16, 1/32, or 1/64), allowing multiple investors to pool resources. This system enabled even small investors, like blacksmiths and shopkeepers, to own a stake, typically around 3% of a ship’s proceeds, creating a diversified investment model.

The “lay system” further mirrored modern equity structures. Crew members, from captains to greenhands, were paid not in wages but in “lays”—fractional shares of the voyage’s net profits, similar to stock options. For example, on the Benjamin Tucker’s 1851 voyage, a captain with a 1/10 lay earned $4,532, while a greenhand with a 1/200 lay earned $226.60 from $45,320 in net proceeds. This profit-sharing aligned incentives, much like modern startups, and spread risk across investors and crew, laying the groundwork for venture capital and stock market principles.

Venture Capitalists in Whaling

Whaling agents acted as the first venture capitalists, intermediating between wealthy investors (limited partners) and captains (entrepreneurs). Agents like Charles W. Morgan, a Quaker merchant born in 1796, were pivotal. Morgan financed and organized voyages, conducted due diligence using logbooks to track successful captains and hunting grounds, and enforced secrecy akin to modern NDAs.

Agents raised capital, hired crews, outfitted ships, and sold the catch, typically retaining 25–33% of a venture’s equity and charging fees for services, similar to the “2 and 20” model (2% management fee, 20% carried interest) in modern venture capital.

Agents diversified risk by pooling funds from multiple investors—on average, eight per New Bedford ship—and spread investments across several voyages. This syndication mitigated the high failure rate, as about one-third of voyages returned zero or negative profits. Successful agents, like modern VCs, built reputations for selecting top captains and crews, ensuring consistent returns.

Top Successes in Whaling

The whaling industry’s “golden age” (1818–1853) saw remarkable successes:

- 1853 Peak: The industry generated $11 million in sales, with a single voyage sometimes yielding profits over $100,000. For example, a retrofitted vessel in 1847, costing $8,000, returned $138,000 after four years.

- Gideon Allen & Sons: This New Bedford agency achieved an extraordinary 60% annual return during much of the 19th century, far above the industry average of 14%.

- Charles W. Morgan’s Fleet: Morgan’s ventures were highly profitable, and his eponymous ship, launched in 1841, completed 37 voyages over 80 years, surviving storms and attacks.

- Nantucket’s Dominance: By 1829, Nantucket’s fleet grew from 6 sloops in 1715 to 203 vessels, expanding to 552 by 1840, driven by innovations like onboard tryworks.

These successes highlight the industry’s ability to generate outsized returns despite high risks, akin to modern VC-backed “unicorns.”

The Concept of Capital in Whaling

Capital in whaling was both financial and human, structured to manage extreme risk:

- Financial Capital: Voyages required substantial upfront investment for ships, equipment, and provisions. Agents raised funds from wealthy individuals, professionals (e.g., doctors, lawyers), and small investors, creating a diversified capital pool. Shares were rarely traded, ensuring investors were committed for the voyage’s duration.

- Human Capital: Experienced captains and crews were critical. Agents selected captains based on track records, as their leadership determined success. Crews, including diverse groups like African Americans and Native Americans, were incentivized through lays, aligning their efforts with investors’ goals

- Risk Management: Diversification across multiple voyages and the lay system spread risk. Agents also purchased insurance, often from firms they owned, to protect against losses. The industry’s capital-intensive nature and long-term horizons (voyages lasted 3–10 years) made it a natural experiment in high-risk investment, mirroring modern VC dynamics.

Top Investors in Whaling

While individual investor names are less documented, key figures and firms stood out:

- Charles W. Morgan (Philadelphia/New Bedford): A leading agent, Morgan financed multiple voyages and owned a fleet, including the Charles W. Morgan, now a preserved museum ship. His investments in whaling and later in General Electric (as an early adopter of Edison’s lights) showcased his VC-like foresight.

- Hetty Howland Green: Known as one of America’s richest women, Green inherited wealth from her family’s New Bedford whaling agency. Her investments extended beyond whaling, but her family’s success in the industry was notable.

- Gideon Allen & Sons: This agency’s 60% annual returns made it a top performer, attracting capital from New Bedford’s elite.

- Nantucket Quakers: Families like the Rotchs and Macys (including Rowland Hussey Macy, founder of Macy’s) invested heavily in whaling, leveraging their community’s financial networks.

- James Fenimore Cooper: The novelist invested in a Sag Harbor whaling firm in 1818 but incurred a loss, illustrating the industry’s risks.

These investors, often Quakers, combined financial acumen with risk tolerance, much like modern venture capitalists.

Business Model of Whaling

The whaling business model was innovative and structured to maximize returns while mitigating risks:

- Syndication: Agents pooled capital from multiple investors, dividing ownership into shares (e.g., 1/16 or 1/64) to fund voyages costing $20,000–$30,000.

- Lay System: Crews were paid a share of net profits (lays), ranging from 1/10 for captains to 1/250 for greenhands, incentivizing performance without fixed wages.

- Agent Role: Agents organized voyages, selected captains and crews, outfitted ships, and sold products (oil, baleen, spermaceti). They charged fees (e.g., for provisioning) and took 25–33% equity, earning profits even on less successful voyages.

- Risk Diversification: Investors spread capital across multiple ships, and agents insured ventures, reducing exposure to losses.

- Onboard Processing: By the 1750s, tryworks (brick ovens for rendering blubber) were installed on ships, enabling longer voyages and higher profitability by processing oil at sea.

This model, with its equity-like compensation and risk-sharing, closely resembles modern VC partnerships.

Top Captains

Successful captains were critical to whaling ventures, akin to startup founders:

- Valentine Pease (Edgartown): Captain of the Acushnet (1841), where Herman Melville served. Pease’s leadership earned him a 1/175 lay.

- Abner P. Norton (Victory): Killed by a whale in 1829, Norton was a skilled captain whose death highlighted the job’s dangers.

- Thomas Welcome Roys: Pioneered Arctic whaling via the Bering Strait in 1848 and invented the rocket harpoon, boosting efficiency.

- Elisha Folger (Friendship): A Quaker abolitionist, Folger employed escaped slaves like Prince Boston, showcasing inclusive hiring.

- George Pollard Jr. (Essex): Despite the Essex’s 1820 disaster, Pollard’s earlier successes marked him as a capable leader.

These captains were selected for their track records, navigational skills, and ability to manage diverse crews, much like VCs choose proven entrepreneurs.

Ships Used in Whaling

Whaling ships evolved to meet the industry’s demands:

- Early Vessels (17th–18th Century): Small sloops (38–50 tons) were used in Nantucket, manned by 12–13 men, often Native Americans.

- Merchant Ships (18th–Early 19th Century): Double-hulled, reinforced vessels (250–350 tons) carried equipment and crews, with heavy armament for defense.

- Barks and Clippers (19th Century): Purpose-built barks (30–45 meters, 300–400 tons) and clipper ships became common in the 1850s, equipped with tryworks for onboard oil rendering.

- Notable Ships:

- Charles W. Morgan (1841): A 351-ton bark, it completed 37 voyages, surviving decades of service.

- Essex (1819): Sunk by a sperm whale, its story inspired Moby-Dick.

- Acushnet (1841): Carried Herman Melville and was typical of sperm whaling vessels.

- Ann Alexander (1851): Stoved by a whale, mirroring the Essex’s fate.

- Whaleboats: Small, 7–9-meter cedar-plank boats launched from the mother ship for hunting, manned by harpooners and boat steerers.

Ships were designed for durability and cargo capacity, with innovations like try works extending voyage profitability.

Deals Made in Whaling

Whaling deals were structured as partnerships:

- Equity Shares: Investors bought fractional shares (e.g., 1/16) in a voyage, with agents retaining 50–70% of profits.

- Lay Agreements: Crew contracts specified lays (e.g., 1/10 for captains, 1/200 for greenhands), deducted for supplies or violations.

- Agent Fees: Agents charged fees for outfitting and provisioning, often taken from gross proceeds, ensuring profits even on failed voyages.

- Insurance Deals: Agents sold insurance through firms they owned, hedging risks for investors.

- Syndication: Agents pooled capital from 8–12 investors per ship, spreading risk and enabling large-scale ventures.

- Notable Example: Charles W. Morgan’s logbook NDAs ensured captains kept hunting grounds secret, protecting competitive advantages.

These deals aligned incentives, diversified risk, and maximized returns, mirroring modern VC term sheets.

Recent Results and Legacy

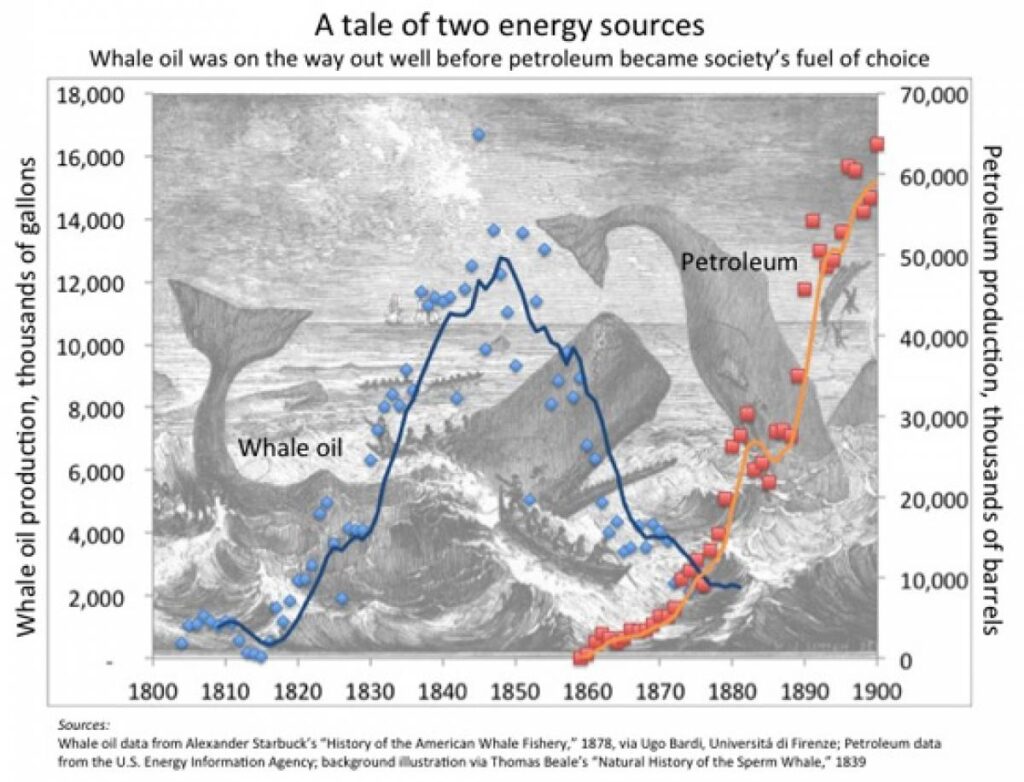

By the late 19th century, whaling declined due to overharvesting, petroleum’s rise (1859 onward), and economic shifts. The last U.S. whaler, John R. Mantra, sailed from New Bedford in 1927. However, whaling’s financial innovations endure:

- The lay system inspired modern stock options and equity-based compensation.

- Agents’ syndication and risk management laid the groundwork for venture capital, influencing Silicon Valley’s rise.

- Investors like Morgan transitioned to other industries (e.g., textiles, retail), with descendants like Rowland Hussey Macy founding modern corporations.

Today, whaling is limited to a few countries (e.g., Iceland, Japan, Norway) under strict regulations, with the International Whaling Commission banning commercial whaling in 1986. The industry’s legacy lives on in venture capital’s risk-reward model and America’s entrepreneurial spirit.

Current Business Houses in the Whaling Industry

Iceland

In Iceland, commercial whaling is conducted on a small scale, primarily targeting minke and fin whales within the country’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). The industry is closely linked to fishing, with companies often processing both whale and fish products in shared facilities. Key business houses include:

- Hvalur hf: Iceland’s primary whaling company, based in Hafnarfjörður, is the most prominent player in the country’s whaling industry. Led by Kristján Loftsson, its managing director and a key shareholder, Hvalur hf focuses on hunting fin whales, an endangered species, and has exported over 2,800 metric tons of whale meat to Japan since 2008. The company also holds permits to process, cut, and pack whale meat alongside fish products at its facilities. Hvalur hf has shareholding ties to HB Grandi, a major Icelandic seafood company, where Loftsson serves as chairman. These ties include ownership stakes held by Hvalur hf, Hampiðjan (a fishing gear manufacturer), and Fiskveiðihlutfélagið Venus ehf, which together owned 53.2% of HB Grandi’s shares as of 2012.

- Hrafnreyðar ehf: Another Icelandic company based in Hafnarfjörður, Hrafnreyðar ehf holds permits to process both whale meat and fish, reflecting the integration of whaling with the broader seafood industry. It is less prominent than Hvalur hf but contributes to Iceland’s small-scale whaling operations.

- Hampiðjan Group: While primarily a fishing gear and ropes manufacturer, Hampiðjan is linked to whaling through its board member Kristján Loftsson and its investments in HB Grandi and Hvalur hf. The company’s 2012 annual report highlights its role as a backbone shareholder in HB Grandi, alongside Hvalur hf, illustrating the overlap between whaling and fishing industries in Iceland.

Iceland’s whaling is controversial, with companies like Waitrose, Marks & Spencer, and Findus Group refusing to trade with businesses linked to commercial whaling, citing ethical concerns. Despite this, Hvalur hf and related firms continue to operate, supported by domestic quotas and exports to Japan.

Norway

Norway, which lodged a formal objection to the IWC moratorium, conducts commercial whaling for minke whales within its EEZ. The industry is small, with fewer than 20 vessels registered in recent years, and is often integrated with fishing operations. Key business houses include:

- Hopen Fisk AS: A Norwegian company actively engaged in processing and selling whale meat, Hopen Fisk is a notable player in Norway’s whaling industry. It operates alongside its seafood processing activities, reflecting the shared infrastructure between whaling and fishing.

- Athena Seafoods: This company is a major shareholder in Hopen Fisk, linking it indirectly to whaling. Athena Seafoods focuses on seafood but supports whale meat processing through its investments, highlighting the interconnected nature of these industries in Norway.

- Lofotprodukt AS: A Norwegian seafood company, Lofotprodukt AS sells whale meat through its website and has developed whale meat products like Vestfjordskinka, a whale-meat “ham.” It was a finalist in the Seafood Prix d’Elite for its fish burger, showing its dual role in seafood and whaling.

- Myklebust Hvalprodukter: A family-owned company, Myklebust Hvalprodukter is one of Norway’s leading whale meat processors, with a history dating back to 1920. It supplies whale meat to domestic markets and for export, particularly to Japan, and also produces pet food from whale byproducts. The company emphasizes sustainable whaling and operates under Norway’s IWC-reported quotas.

Norway’s whaling industry has faced criticism for its environmental impact, with 2020 being the deadliest season in years, according to the Animal Welfare Institute. Despite declining domestic demand for whale meat, these companies continue operations, supported by exports and integration with fishing.

Japan

Japan resumed commercial whaling in 2019 after withdrawing from the IWC, focusing on minke, sei, and Bryde’s whales in its domestic waters. The industry is heavily subsidized, as demand for whale meat has plummeted, with thousands of tons of unsold meat from “scientific whaling” stockpiled. Key business houses include:

- Kyodo Senpaku Co., Ltd.: Japan’s primary whaling company, Kyodo Senpaku operates the country’s commercial whaling fleet, including the factory ship Nisshin Maru. It conducts hunts in Japan’s EEZ and previously in the Antarctic under “scientific whaling” programs. The company processes whale meat for domestic consumption and pet food, though much of its product remains unsold due to low demand. Kyodo Senpaku is supported by government subsidies and works closely with the Institute of Cetacean Research, which oversees whaling logistics.

- Nihon Suisan Kaisha (Nissui): While primarily a seafood conglomerate, Nissui has historical ties to whaling and processes whale meat alongside fish products. Its involvement is less direct than Kyodo Senpaku’s but reflects the overlap between Japan’s fishing and whaling industries.

Japan’s whaling is driven more by cultural and political motives than economic viability, as public appetite for whale meat is low, and excess stocks accumulate.

Conclusion

The whaling industry, often called “Whaling Ventures,” was a crucible for modern capitalism. Its business model, with syndicated investments, equity-like lays, and risk diversification, pioneered venture capital. Agents like Charles W. Morgan and firms like Gideon Allen & Sons achieved remarkable returns, while captains like Thomas Welcome Roys drove innovation.

The industry’s ships, from the Charles W. Morgan to the Essex, and its deal structures prefigured modern financial systems. Whaling’s high-risk, high-reward nature not only powered the Industrial Revolution but also shaped the financial frameworks that fuel today’s startups, from Silicon Valley to beyond.

Comments